The director of California’s mental health commission traveled to London this summer courtesy of a state vendor while he was helping to prevent a $360 million budget cut that would have defunded the company’s contract.

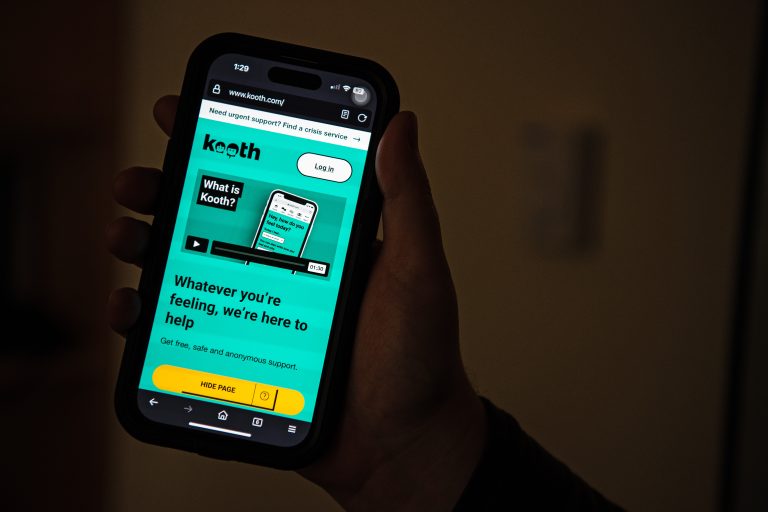

Emails and calendars reviewed by KFF Health News show Toby Ewing, executive director of the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission, made efforts to protect funding for Kooth, a London-based digital mental health company the state hired to develop a virtual tool to help tackle its youth mental health crisis. Ewing pressed key legislative staffers to maintain its contract, even as Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom and lawmakers proposed cuts in the face of California’s $45 billion deficit.

When Ewing and three commissioners — Mara Madrigal-Weiss, the commission chair; Bill Brown; and Steve Carnevale — left for London in June, Ewing wasn’t sure whether he had saved Kooth’s funding. On the second day of their trip, staff informed him that lawmakers had restored the money.

A few days later, he emailed Kooth Chief Operating Officer Kate Newhouse suggestions he had shared with Assembly and Senate staff to improve Kooth’s youth teletherapy app. “We expect you to be involved in whatever we dream up,” Ewing wrote to Newhouse in another email.

It’s unclear why Kooth picked up a $15,000 tab for state officials to travel to London. It’s also unclear why Ewing pushed to protect its app from a spending cut. The commission is a 16-member independent body appointed by various elected officials to help ensure funds from a millionaires tax are used appropriately and effectively by counties for mental health services. Kooth’s contract is with the Department of Health Care Services, which is separate from the commission.

Kooth last year signed a four-year $271 million contract to create Soluna, a free mental health app for California users ages 13 to 25. The app, along with another, by the company Brightline, for younger users, launched in January to fill a need for young Californians and their families to access professional telehealth for free. It’s one component of Newsom’s $4.7 billion youth mental health plan.

Ewing, who reports to the commission, started in 2015 and earned $175,026 in 2023, according to The Sacramento Bee. He was placed on paid administrative leave in September pending an investigation. Commission chief counsel Sandra Gallardo said the commission does not comment on personnel matters. Ewing did not respond to requests for comment.

Three commission employees filed whistleblower complaints against Ewing in September with the California State Auditor. They spoke with KFF Health News on the condition that their names not be used due to fears of workplace retaliation. They say Ewing’s conduct advancing a private company’s agenda as a public official crossed a line.

The agenda for Thursday’s commission meeting listed a personnel matter to be discussed in closed session. The whistleblowers said Ewing is the subject of the discussion.

Madrigal-Weiss said she couldn’t comment on Ewing’s actions. However, she said the commission supports virtual mental health resources for youth.

“These resources are less expensive and have proven valuable for youth, especially those who struggle to access services in typical brick-and-mortar spaces,” said Madrigal-Weiss, who is also executive director of student wellness and school culture for the San Diego County Office of Education.

Brown and Carnevale didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Kooth is committed to advancing youth access to behavioral health services, said Caroline Curran, of Metis Communications, a public relations firm representing Kooth.

“As a leader in youth behavioral health services with over 20 years of experience in the United Kingdom and the United States, we regularly convene sector-leading organizations to facilitate learning through sharing expertise and diverse perspectives on youth behavioral health,” Curran said.

As KFF Health News reported in April, the Kooth and Brightline app rollouts have been slow, with few children using them. In May, Newsom proposed a $140 million budget cut. DHCS Director Michelle Baass said in a hearing that it was due to low use, but the state expects more users to come on board over time.

She told lawmakers on May 16 that roughly 20,000 of the state’s more than 12.6 million children and young adults had registered on the apps, and they had been used for only about 2,800 coaching sessions.

State Sen. Caroline Menjivar (D-Van Nuys) asked Baass at the hearing whether “there’s room to get out” of the contract altogether. Senators later voted unanimously to cut the entire platform budget to save the state $360 million.

Ewing texted a colleague on June 3: “Kooth is freaking out. Is the cut coming from the Admin or the Leg.? Do we know if it’s a done deal?”

State lobbying records show Kooth has paid around $100,000 this year to the firm Capital Advocacy. At the same time, Ewing’s emails and calendars show that he pushed for Kooth’s funding to be retained. For instance, his June 4 calendar shows he was scheduled to meet with Laura Tully, an executive from Kooth USA, at a coffee shop near the Capitol.

The next day, a whistleblower said, Ewing met with key Senate staff members: Scott Ogus, deputy staff director of the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee, and Marjorie Swartz, a consultant for Senate President Pro Tempore Mike McGuire. They said Ewing also discussed Kooth’s contract that week with Rosielyn Pulmano, a health policy consultant for Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas.

“Toby kept saying that ‘California has to have a digital strategy,’” recalled the whistleblower, who attended both meetings. “He kept pushing Marjorie and Scott, saying that he would give them ideas to make the platform better.”

Ewing emailed ideas to the legislative aides on June 10 and 12.

About two weeks later, he and the commissioners left for the seven-day trip to the U.K. According to documents filed with the state Fair Political Practices Commission, receipts, and emails reviewed by KFF Health News, Kooth covered the costs of four-star hotels, meals, train tickets, and international flights.

Public disclosure forms show Kooth paid expenses for Ewing, Madrigal-Weiss, and Brown. The forms do not show the company paid for Carnevale’s travel.

Under California law, state officials generally must report travel payments to the FPPC, which Ewing and his fellow commissioners did.

Kooth postponed a mental health investment conference in London in June, emails and documents show, but then organized new events for the California commissioners to attend instead.

On May 23, Newhouse informed Carnevale and Ewing in an email that Kooth needed to postpone the planned June event. Carnevale, a venture capitalist, described the news as “disappointing for all,” especially “because we have already booked trips, including family members of Commissioners who were planning to turn this into a holiday.”

Acknowledging the disruption, Newhouse told Carnevale that she “would like to think creatively as to whether we could try to arrange a meeting where you can talk about the CYBHI,” referring to Newsom’s Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative.

“I know though from our conversation that we need to cover the ‘purpose’ of your trip and not sure what is possible or not,” she wrote.

Curran, the Kooth spokesperson, said the company “adapted by holding a knowledge exchange between representatives from international policy institutes, research foundations, and non-profit organizations.”

Madrigal-Weiss defended the trip, which she said included meetings with “members of the government, service providers, education, and finance” who shared ideas on how “to enhance funds for public mental health needs” through private and philanthropic partnerships.

One of the whistleblowers said many of the commissioners back in California were not aware of the trip until their colleagues were halfway across the world. Sami Gallegos, a spokesperson for the California Health and Human Services Agency, said the Department of Health Care Services did not participate in the travel.

Ewing was put on leave before Kooth’s rescheduled conference this month in London.

Although it’s not unusual for state officials to travel overseas — often on the dime of private entities — it doesn’t look good, said Sean McMorris, a government ethics expert with California Common Cause, a nonprofit government watchdog group.

“It looks like undue influence,” McMorris said. “I think a lot of people would view something like this as a way to curry favor. You can connect the dots.”

Kooth has similarly gifted travel to state officials in Pennsylvania, where it had a $3 million contract with 30 school districts. In each case, Kooth invited the officials to speak to highlight their work. Pennsylvania has informed Kooth it intends to terminate the contract.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

#California #Official #Helped #Save #Mental #Health #Companys #Contract #Flew #London

A California Official Helped Save a Mental Health Company’s Contract. It Flew Him to London.